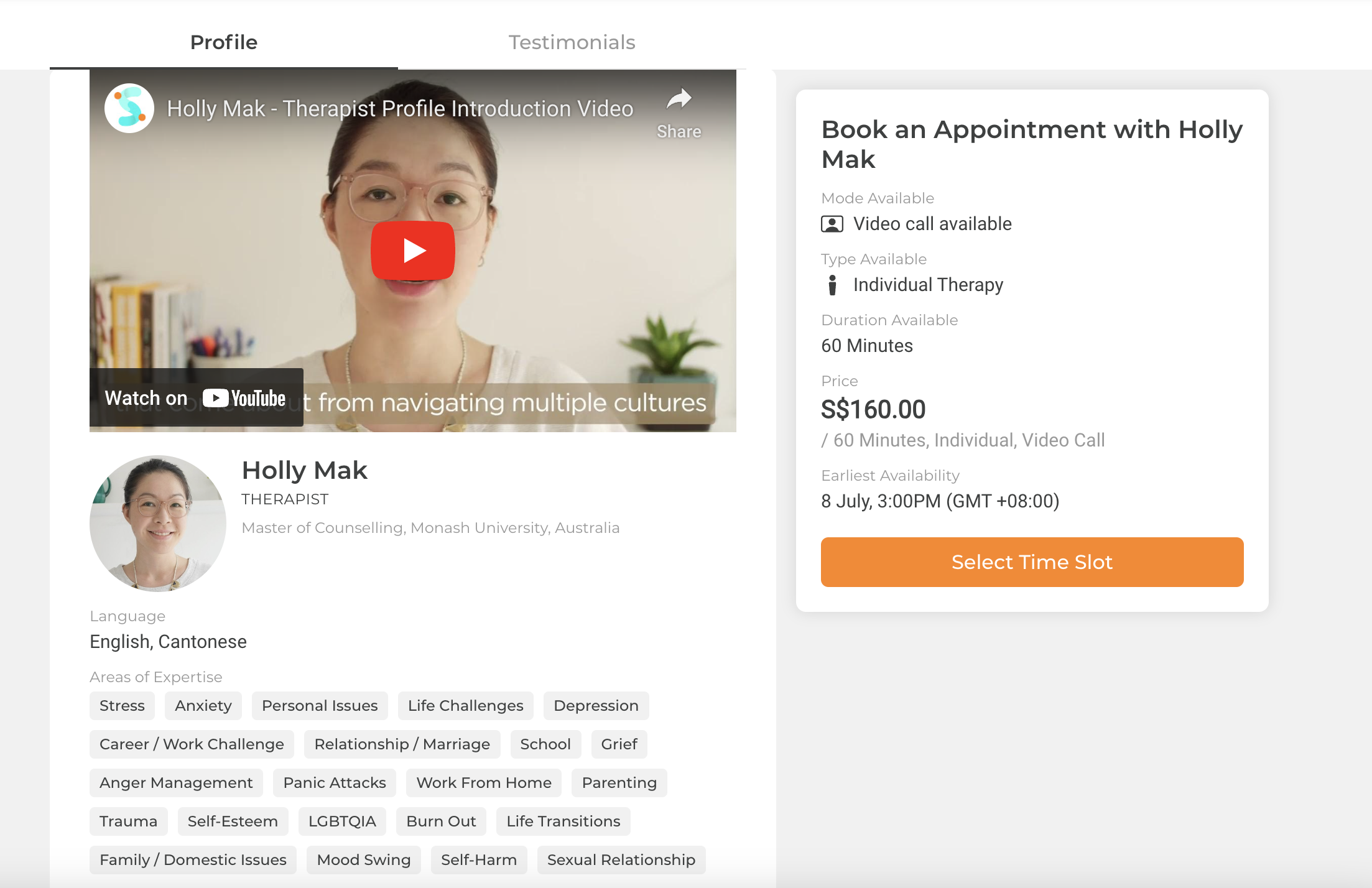

Written by Holly Mak (PSYCHOLOGIST, THERAPIST) | May 10, 2023

“Oh, my god. I can’t believe I just said that. He probably hates me now.”

“Why am I so stupid? Why can’t I do anything right?”

“Wow, how do you not know something so basic?”

“What an idiot.”

Sound familiar? Whether on the giving or receiving end of these statements, we’ve likely all been there before. Shame can permeate our everyday interactions, be it in our own heads, at work, or at home. While it can often go unnoticed, it can still affect us deeply.

So how do some people end up regularly experiencing the above or similar thoughts, and get stuck in a seemingly endless loop of low self-worth?

It may not seem obvious, but shame lies at the root of many difficult emotional and social experiences, and can be built into the very way we see ourselves and the world. Like any emotional habit, feelings of shame often begin early on in life in our childhood and adolescence, often carrying through into our adult relationships and self-perception if unchecked.

Image source: Private Therapy Clinic

What is shame?

The dictionary definition of shame is “a painful feeling of humiliation or distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behaviour.” Shame is not quite the same as guilt though, where we feel bad about a specific choice or action we’ve made. It’s much more pervasive and penetrates into the very core of our beings. Shame has us feeling like something we’ve done or said makes us essentially a bad person – that we deserve rejection and abandonment from those around us.

Shame is universal, as we are social beings and require a community around us in order to survive. Our fear of rejection motivates us to change and adapt our behaviours, for both our own sakes and that of the groups that sustain us. But taken to the extreme, this fear can significantly limit our beliefs and choices, and shut us down.

Internalised shame: When falsehoods feel true

In certain cultures, particularly ones that emphasise collectivism and hierarchy, shame is often normalised. These cultures tend to prioritise the wellbeing of groups over the individual’s, and of elders over their younger counterparts. In Asian families, the general assumption is that it’s wrong to challenge someone more “senior” than you, like a parent or grandparent, even if they’ve said or done something hurtful.

As a result, we might internalise negative feedback that we hear about ourselves, believing that it’s true that we can’t do anything right, that we are less intelligent than our siblings, that we’ll never find a loving partner, etc – when these thoughts are often unfounded.

Tools to overcome shame

Recognising what shame looks like on an everyday basis can help us disarm it, and tune into our true self-worth. We are never born with shame; it is a feeling we cumulate from the outside.

1. “Shoulds” and “Shouldn’ts”

Shame operates on the judgement that we “should” or “should not” do things a certain way, and measures our value based on whether we abide by these standards. Identifying shaming voices and behaviours can help us step back and clarify where we stand, and prevent us from believing we are worse than we are.

Some examples of shaming behaviour:

- Rolling eyes

- Scoffing impatiently

- Pointing or laughing someone at someone

Shaming voices:

- “You should know better than this.”

- “You shouldn’t talk so much. No one wants to hear what you have to say.”

- “How could you get this wrong?”

2. Remember: It’s not about you

If you hear or see any of the above, know that you don’t deserve to. The person shaming you has been shamed themselves, and their shaming you shows that they haven’t processed their own hurt. They aren’t the final judge or authority on your life – you are, which means you are free to let go of whatever they project onto you.

3. Nurture yourself as you would a child or friend

Everyone, including adults, needs to hear words of encouragement and motivation, like “no worries, try harder next time”, or “you got this! I believe in you!” By addressing ourselves with kindness, understanding and compassion, we can have a more realistic view of ourselves – one that can balance room for growth and contentment with our positive qualities.

To conclude: let’s learn to recognise shame from love. Whilst shame sets out unrealistic conditions for earning love, real love is always nurturing and empathetic, allowing a person to exist freely. The antidote to shame is not to simply fulfil others’ expectations for what they think is right for you, but rather, to familiarise yourself with your own values, needs and wants, and be your own biggest cheerleader.